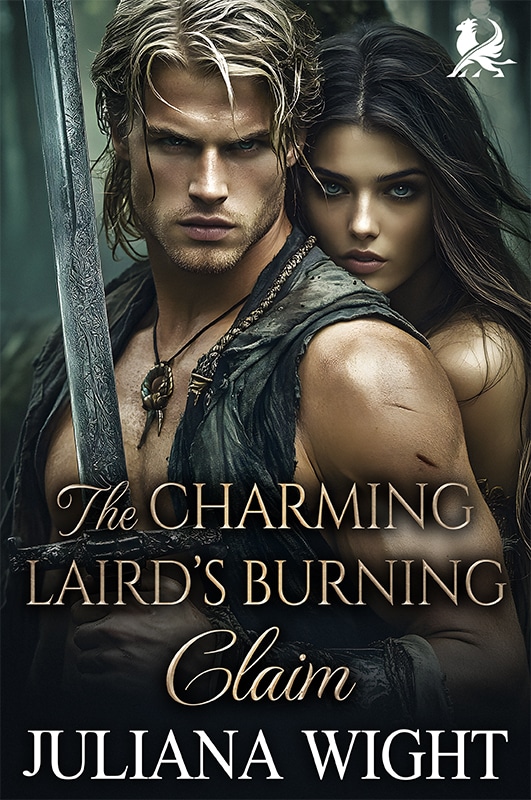

The Charming Laird’s Burning Claim (Preview)

Chapter One

Beaumont Estate, 1715

Odette Beaumont was already on her feet, toes brushing the cold stone floor as she tugged her dressing gown tighter, the morning sun not yet generous with its warmth. Her long, blonde hair was still half-pinned, the rest tumbling in stubborn waves down her back, and she had not yet touched the basin of water meant to greet her waking. There was no time. There never was.

She yanked open the shutters to a dawn streaked in silver, the light glinting across the wide, lonely land she was forced to call home. The Beaumont estate stretched beyond what the eye could measure, but it was land slowly being choked by darkness and decay. But that morning, their salvation would come in the form of Nevil Hillam.

Even the name clanged in her head like iron dropped onto marble. He was due to arrive by noon, a man with enough property to silence most councilmen, and just enough charm to pass for appealing, though Odette had never seen him in person. She had only heard of him from Sheona’s lips, while her stepmother taught her daughters, over afternoon tea, all the ways to trap a man like him.

Odette moved quickly, folding out of her sleep-wrinkled linens with military precision. Her gown slid off her shoulders in one swift motion, and she dressed in a cream working dress, before her hair was fully secured with a blue ribbon behind her head. She left her room without ceremony, door swinging wide as she strode into the corridor. The floorboards groaned underfoot, but she didn’t wince. She’d grown used to those groans. If the house wasn’t complaining, she’d worry it had finally given up.

Nevil owned the land that pressed against the Beaumont estate borders. If his acres married theirs, they might finally tear their lands from the Galbraith clan’s grasp. That was the current Beaumont strategy, the one Odette had overheard Sheona preparing for the past few years.

In the grand hall, the light through the arched windows bled golden across the dusty floors. She paused, taking stock.

That was where Nevil would first step foot. She saw it clearly—the muddy boot prints, the scuffs on the wainscotting, the way the dust danced in the morning light, ready to betray every untended surface.

And Odette, the sole biological Beaumont daughter, had been reduced to little more than a maid. A head maid at best, accountable for every speck of dust that dared settle on any surface. Today, of all days, everything had to be flawless.

Sheona had always insisted that the inheritance left behind by her father, the late Louis Beaumont, was hers alone to manage. Not one coin, not a parcel, had been left in Odette’s name. “Yer faither didnae believe in daughters as heirs,” Sheona had once said with a smug shrug, draped in mourning silk that had cost enough to feed the tenants for half a year.

Odette had accepted it at the time. She had been young, scared and foolishly obedient, her grief over her father’s death leaving no room to consider the consequences of being left penniless and alone.

With a deep breath, she rolled up her sleeves and got to work. Her arms started to ache halfway through sweeping, but she pressed on. The rugs were beaten, the banisters polished until they reflected her face. In the dining hall, she rearranged the chairs three times before they felt right, then set to polishing the silver until it gleamed like a second sun. She opened the tall windows, letting in the scent of summer-laced grass and the soft rustle of garden life.

The garden. It needed to be perfect.

A picnic had been suggested by Sheona with her usual flippant grace, a casual thing said with a velvet-bound voice. But it meant more work. Odette paced through the hedgerows and flower beds, rearranging cushions, checking for bees’ nests in the seats, retying the canopies in tighter knots, pulling weeds with her bare hands.

By the time she finished, her palms were streaked with green, her back damp from effort. Still, she couldn’t stop. She rushed inside, carefully washing and drying her feet before, to avoid smudging the pristine floors, then made her way to the kitchen. Her stomach growled once, but she ignored it. The cook should have been halfway through the preparations by now.

Instead, she was met with chaos.

“Didnae I tell ye, ye fumble-fingered nyaff?” The cook’s voice cracked like a whip across the kitchen, aimed at some cowering maid.

The cook’s face was the color of overripe plums from the oven’s blistering heat and a lifetime of shouted orders. Arms thick as rolling pins carved through the flour-dusted air, sending clouds swirling in their wake as she bellowed at the staff.

Her two assistants scrambled about like cornered hens, all twitchy limbs and darting glances, their aprons flapping as if the devil himself were at their heels. The clang of copper pots dueled with the hiss of boiling stock, but the cook’s voice cut through it all, like razored steel against the kitchen’s roar. Then those flinty eyes locked on Odette.

A derisive snort escaped her before she made a failed attempt at composing herself. “Dinnae look at me like that, Miss Odette. I told the girls yesterday—we’re out o’ nutmeg, we’re out o’ sugar, and the butcher delivered lamb instead o’ quail. Lamb! Fer a picnic!”

Odette didn’t blink. “Give me the list.”

Cook blinked, startled. “Ye’ll go yerself?”

“Unless you’d like to present roasted lamb for the picnic.”

The cook thrust the list at her, muttering under her breath, and Odette turned on her heel and headed toward the grand entrance. She was halfway to the door, breath already picking up with the anticipation of a sprint to town, when two high-pitched voices trilled down the hall.

“Odette!”

“Odette! Wait!”

Celeste first, all powdered cheeks and manicured hands, followed by Vivienne with her sharp eyes and the silken sneer she thought was subtle. They were already impeccably dressed, with corsets too tight, hair pinned in elaborate nests and lips like bleeding cherries. Odette stilled. She knew that tone, and she cursed herself for not leaving the house a little earlier, before they’d had a chance to see her leave.

Vivienne reached her first. “Ye’ve nae fixed the hem o’ me gown, and I want it ready fer the luncheon before—”

Celeste interrupted, “And I cannae find the sapphire comb. The one we brought back from Elmsport? I need it. And the ribbon box—have ye even looked? I told ye days ago.”

“Ye havenae cleaned me room,” Vivienne added, as if the realization offended her.

Celeste brightened. “Or mine! And Maither said we should each bring a token fer Mr. Hillam. Something thoughtful. Like poetry, maybe? Or an embroidered kerchief? Ye can dae one fer each o’ us. Ye’re good with thread.”

“And words.”

The list spiraled impossibly fast, like a fever dream. Odette did not flinch. She stood very still, the market list in her fingers like a blade.

“If you keep me here, there will be no food on the table when Mr. Hillam arrives. There will be no tokens, no hemmed gowns, no sapphire combs—no picnic.” Odette finally interrupted them, raising a hand to silence their chatter as she struggled to contain her frustration. Losing her temper would only make matters worse.

Vivienne’s brows lifted. “Well, someone’s in a mood.”

“Dinnae take that tone with us,” Celeste huffed. “If ye speak tae us like that again, we’ll tell Mther. Ye ken what that means.”

A flicker of pain, deep in the spine. A ghost-memory of leather across skin, of welts hidden beneath dresses. Odette met their eyes squarely.

“Do what you must. As will I.” And she pushed past them before either could reply.

Outside, the morning had warmed. The sun found her skin, kissing the sheen of sweat that coated her neck and collarbone. The sky stretched open above her, and her boots hit the gravel path with purposeful rhythm. She felt the familiar ache of fury in her chest—a low, ever-burning heat that she had learned to breathe around.

The wind caught her hair as she stepped onto the main road, tugging strands free from the ribbon she’d tied low behind her neck. She didn’t bother to fix it. The market waited for her, and her time was already borrowed. She pulled her shawl tighter around her shoulders and kept her gaze steady, her steps sure.

The town wore suspicion like a second skin. It clung to the buildings, weather-worn and squat, and to the faces of the people who watched from behind carts and cracked shutters. Odette knew how they saw her. Her features were too delicate, her posture too straight, her cheeks too sharply carved, her tongue too quick. She was too foreign to blend in with them—too French. And the town hated the French.

It didn’t matter that she had lived in the Highlands since she was fourteen. It didn’t matter that she had earned her keep and held her tongue. Her voice betrayed her the moment she opened her mouth. Her vowels had edges. So, she spoke as little as she could.

Every errand was a tightrope. The Galbraith lands bristled with men who polished their muskets like sacred relics and saw rebellion in every stranger’s glance. Their hatred of outsiders ran deep as their peat bogs, and they had no patience for women who didn’t know their place. Especially not foreign women with French and Jacobite blood whispering through their veins.

Odette never bowed.

She kept her eyes forward and her steps quick. The grocer’s stall stood first in her path. Lemons. Soft cheese. She pushed open the shop door, its bell jingling with false cheer.

“Well now, good day tae ye, miss.” The grocer’s son leaned against the counter, broad shoulders straining his linen shirt, a smirk playing about his mouth that suggested he found himself endlessly amusing. His gaze swept over her like she was a cut of meat on display. “What can I dae fer ye today?”

She said nothing. Simply raised one finger and pointed to the yellow citrus stacked in woven baskets. His smirk faltered. An awkward beat passed before he huffed and began bagging the lemons, his thick fingers denting their waxy skins.

When she pointed next to the cheese, a creamy round wrapped in muslin, he snatched it up without meeting her eyes this time, his earlier charm curdling into irritation.

Coins clinked against the counter as she paid. As he counted out her change, she caught his muttered words, “Bloody odd, some folk…”

The insult hung in the air between them, sour as the lemons in her basket.

Odette pocketed the change without reaction. Pride was for those who could afford it—for women who hadn’t been whipped by their stepmothers two days prior.

The baker was next. The girl behind the counter wouldn’t meet her eye. That was fine. Odette didn’t need friendship. She needed flour. It wasn’t until she reached the end of the row of shops, where the butcher’s stood with its sagging sign and smoke-scented walls, that she allowed herself to breathe more deeply.

Maria, the butcher’s wife, greeted her with a warm smile from behind the counter, hands still dusted with salt. Her dark hair was pulled back in a braid, her apron worn through at the hips. She looked tired, but kind. She was always kind.

“Ye look flustered today,” Maria said, wiping her hands on a cloth.

“It’s been quite a day today,” Odette replied with a faint smile. “I have come to buy some quails, for the picnic.”

The two children—Niall and little Tom—darted out from the back room like arrows. Tom hugged Odette’s legs with the enthusiasm of a pup, and she reached down to ruffle his hair. Niall simply grinned at her from behind a row of smoked sausages.

“How is the madhouse today?” Maria asked, moving behind the counter and beginning to wrap parcels.

Odette exhaled through her nose. “Vivienne has a list of demands for me before noon, Celeste is looking for fine jewels, and Mr. Hillam arrives by noon.”

“May the saints protect ye.”

“They’ve stopped answering me letters.”

Maria laughed. The sound was rough and real. It softened Odette in places inside her soul she didn’t realize had gone stiff.

“Still thinking o’ running off?” Maria asked after a moment, quieter now. More cautious.

Odette looked at her, then glanced at the children, who were busy poking at a jar of pickled onions. “I’ve sent a letter,” she said softly. “To my aunt in Lyon.”

Maria stilled. Her dark brows drew together. “That aunt? The one with the bakery near the port?”

“The same. I don’t know if she still lives there. Or if she still thinks of me as family. But if she does…”

Maria nodded. “She will.”

“I asked her for help. A place to stay. Funds, if she can spare them.”

“And if she daesnae reply?”

Odette wrapped her arms across her chest. “Then I will think again. But I had to try.”

Maria looked at her for a long time, then passed over the wrapped parcel of meats and dry sausages. “Ye deserve more than that house. More than scraps and silence.”

“We all do.”

The door creaked open behind them. Three men stepped inside.

They were not locals. Odette knew that before they spoke by the way they carried themselves, like they expected space to be cleared for them. Their coats were long, travel-stained, their boots laced in a style she hadn’t seen in months. One of them, taller than the others, had a scar across his chin that looked recent.

“We need supplies,” the tallest said, voice low and hard. “Dry meats. Cuts that keep. And nay fuss.”

Maria’s smile faltered. “Aye. I’ve some salted pork and beef left from last week.”

The man gave her a cursory nod, eyes already moving over the room. When they landed on Odette, they paused.

“Ye from here?” he asked.

Odette met his gaze evenly, then nodded.

The man stepped closer. Not threatening, exactly. But not friendly either. “Where from?”

“Nearby,” she said. Clear. Calm.

He stared at her for a moment longer, then snorted. Maria moved quickly, placing a wrapped parcel on the counter.

“Here. That should hold ye through the week. It’s all I have until Friday.”

The men exchanged a glance. The one with the scar dropped coins on the wood, never looking away from Odette. Then, the man smiled, slow and ugly. But he turned and walked toward the door. The three of them left without another word and the door shut behind them like a falling axe.

Maria exhaled. “Saints. Odette—”

“I know.”

Maria reached across the counter and touched her hand. “Just go home. Dinnae linger too long.”

Odette nodded. She gathered the parcels, kissed both children and stepped back into the wind.

Chapter Two

Odette clutched the heavy parcels against her chest, her shawl slipping down her shoulder as she half-walked, half-ran down the lane, boots thudding against the damp earth. She cursed herself under her breath for wasting time, though the words came out in little puffs of steam. Idiot. Foolish, chattering idiot. What had possessed her to stay so long? Laughing with Maria like she hadn’t a thousand things left to do. As if that day wasn’t the day the entire household had been waiting for months.

The wind had picked up, dragging the clouds back across the sky and throwing a veil over the sun. Her pulse hammered a frantic rhythm beneath her collarbone, each beat painting the same damning picture of Sheona in the great hall, prematurely lighting the beeswax candles, while Vivienne and Celeste would be draped over their mother’s chaise by now, pouting through rosebud lips about how Odette hadn’t braided their hair with the pearl pins, how the lace at their cuffs hung crooked without her fingers to set it right.

And Nevil Hillam—

The thought struck like icy water. Nevil’s carriage would crest the eastern road in mere hours.

“Damn it,” she muttered, quickening her steps, her boots slipping on the moss-lined cobbles as she veered into a narrower street. Her breath caught sharp in her chest. It wasn’t far now. Just across the green, down the slope. She could be home in twenty minutes if she walked fast.

She was halfway through rearranging her to-do list in her mind—flowers first, then set the table, help Elise with the linens, reheat the broth—when she heard it.

Footsteps.

Heavy, deliberate, just a beat behind her own. She didn’t turn around. Not at first. There were always footsteps behind her in town, weren’t there? People walking, going about their day, minding their business. But something didn’t feel… right. They didn’t match the rhythm of the street. She could hear the click of her own boots, the rustling of her skirts and the echo of something heavier.

Her spine stiffened.

She told herself not to be silly. Town was busy today, as always was on market mornings, and the air smelled of smoked herring and damp wool. Nothing bad could happen in ordinary daylight.

She glanced over her shoulder. Just a flick of her eyes. They were there. The same three men from the shop.

They weren’t near enough to touch her. Not within arm’s reach, and yet they were still too close. Far too close for men who should have been halfway to the tavern by now, considering she’d deliberately lingered in the shop until their footsteps had faded five minutes past.

Sunlight carved their features into something unfamiliar. Indoors, they’d been just rough-faced laborers; out here, the glare sharpened them like knives on a whetstone. The dark-haired one who had spoken to her at the shop, taller than his companions, with a nose that hooked sharply to the left, wasn’t merely smiling. His lips peeled back from teeth that looked too white, too even, in a face weathered by wind and work. It wasn’t a smile at all. It was a predator’s grimace, twisting his already harsh features into something grotesque. The kind of expression that made a woman’s palms sweat and her throat tighten, though she couldn’t say why.

One of the others, shorter and broader, said something low and guttural. The dark-haired man’s smirk widened, and for one terrible second, Odette imagined she could smell the ale on their breath, even across the distance between them.

She snapped her head forward and kept walking, faster now, steps clipped and uneven, eyes fixed on the narrow path ahead.

Don’t panic. You’re imagining things.

She turned down a darker lane. It was narrower than the others, a shortcut only locals used, with crooked little garden gates and several cats underfoot. She hadn’t meant to take it. Her feet had done it without asking her permission. But now that she was there, she tried to see it as a stroke of luck. If they were just going her way, they wouldn’t follow her here. They’d go the long way around, as any normal traveler might.

The road twisted. She passed the blacksmith’s shed, empty at this hour, and a cart of rotten apples, buzzing with flies. She let herself breathe again.

She glanced back. They were still there. All three of them. And they were getting closer.

Her fingers clenched around the string of the package so hard it bit into her skin. She turned down another path. One that made no sense unless you were from there—narrower than the previous, with uneven stones and thorns clawing at your legs. No stranger would know to follow it.

But they did and their boots slapped the stones, louder now. Her chest tightened. She wasn’t imagining it. She was not imagining it.

She sped up. Her arms ached from the weight of the parcels, but she didn’t stop. Her thoughts tangled into knots. Who were they? Why her? She hadn’t looked at them. Hadn’t said a word. Had she done anything to upset them?

She turned again, sharper this time, nearly losing her footing on a patch of gravel. She passed the old garden wall, ducked beneath the low-hanging tree where the crows always nested, and darted into the alley beside the milliner’s, which was narrow enough to make her shoulders brush brick.

When she emerged on the other side, she broke into a run.

The parcels were a hindrance. She clutched them tighter, arms burning, feet slipping, heartbeat hammering so loud she thought it might betray her. But she didn’t stop. Don’t look back. Just move. But she did look. They were running too. And they were faster than her.

No, no, no—

A loose stone caught her foot. She stumbled, arms flailing to catch balance. One bundle tumbled from her grip.

She didn’t even stop to mourn it. She sprinted, still carrying the other parcels.

Skirts flying, loose hair whipping her cheeks, breath ragged in her throat. Her home was still so far, and her feet ached, and the world was too loud.

She turned another corner. Dead end. She skidded to a halt, chest heaving, eyes wild.

No. Not here. Not here.

She spun around. They were there, blocking the only way out. They were silent now, grin gone from the tall one’s face. She backed up against the wall, fingers outstretched behind her, as if the cold stone might offer a way out. Her breath came in frantic bursts, her lungs too small, her heart too loud.

The tallest one spoke.

“Ye dropped yer things,” the words rolled out in a thick brogue, though she couldn’t place the region. Not that it mattered. There was no kindness in that voice, only a rough amusement that put her teeth on edge. She knew the accent well enough, though her own tongue could never wrap around those guttural vowels.

She didn’t answer.

The third one stepped forward. Blond, scruffy. His nose looked like it had been broken and badly set. “Bit o’ a rush, aren’t ye? Something wrong?”

“Yes,” she whispered, though she wasn’t sure they heard her.

The dark-haired one stepped into the center. “Funny how yer people always seem tae run when it’s time tae answer fer what they’ve done.”

Odette blinked. “What?”

He didn’t repeat himself.

“Ye live in that big house on the hill, dinnae ye?” asked the blond one, voice too casual. “With all the little silver spoons and the paintings o’ men who never bled a day in their lives.”

She didn’t reply. Couldn’t. Her voice had hidden somewhere beneath her ribs.

“Me land,” the dark one said, “used tae stretch as far as I could see. Me father built it. Me grandfather fought fer it. And yer fine French soldiers burned it tae ash.”

“Me maither,” added the third, quietest of the three, “died with yer flag above her.”

Odette shook her head. “I—I haven’t done anything. I don’t—my family hasn’t—”

“Yer family has,” said the tall one. “They all have. And ye wear their name.”

He stepped closer. Odette’s back hit the stone, as her fingers scraped rough brick and her heart beat so fast it was a war drum in her ears.

“We’ve waited a long time,” he said. “And now it’s time someone paid.”

Odette’s breath left her lungs in a sharp gasp.

The nearest man grabbed her by the upper arm, his grip vice-like and punishing. Another seized a handful of her hair, jerking her head back so suddenly her neck cracked. A small cry escaped her, shrill and desperate. She kicked at one of them—whoever had his hand at her waist—and he swore, grabbing her tighter. It all happened so fast. Her bundles fell to the ground, parcels bursting open.

“Let me go!” she screamed, twisting in their hold, nails clawing at their arms. She tried to bite one—anything to get them off—but they were too many and too strong for her to take on. Their laughter was cruel and close to her ear, their breath reeking of stale drink and old anger. Rough hands yanked at her shawl, another at the laces of her bodice. Her mind flooded with panic.

This is happening.

It didn’t feel real. It was as if she’d been dropped into someone else’s nightmare, someone else’s pain. Her limbs flailed in a hopeless attempt to break free. She kicked, scratched, screamed again. They slapped a hand over her mouth, but she bit it hard, drawing blood.

“Ye filthy little—!” one of them hissed.

A hand tangled in her hair, and with one wrenching pull, her ribbon snapped loose. The silk fluttered to the ground like a white flag of surrender. But she wasn’t surrendering. Not yet. Not ever. She didn’t stop fighting. Her voice cracked as she tried again to scream for help, her throat raw with the effort.

And then—

“Who’s there?”

A man’s voice, deep and cutting through the chaos like a blade. Not close, but not too far either.

Odette screamed again, louder this time. “Help!” Her voice split the quiet of the alley, bright with desperation. One of the men cursed, slapped her across the cheek hard enough to make her vision white out.

“Shut ‘er up!”

“I hear ye!” the voice came again, nearer now.

Odette fought harder, tasted blood in her mouth, tears streaming freely down her face.

Footsteps. Fast. And then—he was there.

At first, she didn’t know what she was seeing. Just a tall figure, broad and cloaked in shadows, standing at the mouth of the alley with a drawn sword.

“Step away from her,” he said, voice low and deadly.

The men froze. One of them laughed nervously. “And who the hell are ye supposed tae be?”

He took a step forward, sunlight catching on the blade.

“Yer final mistake.”

Then it all happened at once.

The stranger moved with terrifying precision. He disarmed the first man in a single motion, elbowed the second hard enough to send him crashing into a wall. The third ran for him with a dagger, only to find himself flat on his back in the mud within seconds, the weapon skidding away.

Odette crouched against the wall, clutching her arms around herself as the sounds of fists and bone and metal rang out in sickening rhythm. She couldn’t look away. Couldn’t even breathe.

He moved like a controlled but ferocious storm, effortless but wrathful. She couldn’t make out his face clearly, but every line of his body spoke of power, of danger wrapped in grace. The man appeared like something born of storm and legends. Every flex of his muscle, every controlled shift of weight speaking of power that hummed beneath his skin. Where other men lumbered or stumbled, he flowed, his body obeying some silent rhythm only he could hear. Sunlight caught his sharp jawline as he fought, and for one breathless moment, Odette forgot how to think.

Magnificent.

The word burned through her like whisky, leaving her throat tight. He was something primal. As if the old tales of warriors blessed by God had taken flesh before her. She couldn’t tear her eyes away.

Within moments, it was done.

The men groaned on the ground, one crawling, another unconscious. The third tried to get up, but the stranger placed a boot on his back and pressed him down.

“Tell yer friends,” he said quietly. “And if I ever see ye near her again, ye’ll regret drawing breath.”

The man whimpered. The stranger let him go. Odette still hadn’t moved.

He turned to her slowly, sword now lowered, his voice softened. “Are ye hurt?”

She blinked up at him, her mind trying to connect thoughts that wouldn’t hold. Her body was shaking, her breath came in short bursts. Her lip stung, her scalp burned where the man had yanked her hair.

“I’m—” She tried to nod. “I’m fine.”

He didn’t argue. Just looked at her a moment, then glanced at the basket she’d dropped in the scuffle. Loaves spilled, the meat parcel burst open and leaking across the stones. He crouched without a word. His movements were unhurried, not delicate exactly, but careful. Intentional.

She watched as he brushed dirt from one of the loaves with his bare hand, rewrapped the meat with surprising precision, and set them back inside the basket. Then, still kneeling, he pulled a clean, pale linen handkerchief from his coat pocket and unfolded it.

“Ye’re bleedin’,” he murmured, not quite meeting her eyes. “May I?”

Odette opened her mouth, unsure what she meant to say. Her hands were still trembling, but she gave the smallest nod.

He rose slowly and stepped close enough that the heat of him reached her, warmth radiating off his coat, his skin, the steam of his breath in the cooling afternoon. When he reached for her lip, he didn’t touch her. Just held the cloth near her mouth, offering it. Waiting.

She took it with shaking fingers. But when she pressed it to her mouth, her hand faltered. Without thinking, he caught her wrist. Not to still her, just to steady it. His grip was surprisingly gentle, calloused skin against hers.

Her heart stuttered. He guided her hand just slightly, then let go, as if the brief contact had been too much.

God, those hands.

Capable of wielding a broadsword yet now helping her tend a cut no deeper than a papercut with the reverence of a priest at altar. Roughened by war, but startlingly kind. Veins traced rivers of strength beneath sun-bronzed skin, the pulse at his wrist steady where hers fluttered wild as a caged bird. The brush of skin against skin sent a spark up her arm.

His shadowed, dark grey eyes lingered on her. He was tall. Not just tall, formidable. The kind of man who carried weight simply by standing still. His jaw was cut like stone, and his eyes, though unreadable, bore the gravity of someone who’d seen too much but feared nothing.

Odette’s breath caught. This strange flutter in her chest that had no place in this moment.

“I didn’t mean to cause trouble,” she whispered, brushing the tears from her cheeks. Her voice was hoarse. “I was just… heading home.”

She stood too quickly. Her knees buckled, and she nearly stumbled. He reached for her instinctively, one hand at her elbow, but she flinched.

“I’m fine,” she said again, too fast, too sharp.

He stepped back. Her hands shook as she patted her skirts, trying to gather whatever scraps of composure remained. Her ribbon lay in the dirt, but she left it. The thought of bending down, of presenting her back to anyone, even though he was her savior, made her stomach twist

“Thank you,” she said, eyes fixed on the ground. “For helping me.”

“I couldnae ignore yer screams.”

God, that voice. It rolls through me like low thunder before a storm.

“No,” she murmured. “I suppose not.”

She moved past him, legs stiff, shoes crunching on the gravel. She had to leave. Now. Before the tears started again. Before the fear made its way back in. She didn’t give him her name.

The alley spilled out into a narrow street, and she kept walking, faster now, turning sharply left and then right again. She didn’t look back, despite wanting to.

But she heard him.

“Wait—”

Her heart jumped. She kept walking.

“Miss—please—”

She broke into a jog, slipping between two houses, her body moving on instinct. She didn’t know why she ran. He had saved her, not hurt her, but her mind no longer had any trace of rationality. Her fear had roots, and they were deep.

If you liked the preview, you can get the whole book here

Looks interesting indeed…

So happy you think so my dear Kath, thank you! 🙏